My mother was thrilled when I picked up the phone. There was a lilt in her voice. But I didn’t have time to talk and gave her the quick message that my daughter was back. She had wandered in the backyard with her backpack on her back late last night looking to see if she could pitch a tent. She gave me the letter she wrote while on the road, but never could get to a post office to mail it.

Don't they sell stamps in truck stops?

She wrote in her letter of the necessities of life: to eat, to sleep and to shit.

Even though my mother was thrilled I called and my daughter was home, I was afraid to tell her she had hitchhiked with her husband, got rides with truckers who saw them eating in truck stops, then, when they stood by the road, they gave them rides. When they didn’t get rides, they laid their tarp in the ditch so no one could see them and slept.

My little girl with her golden hair and blue eyes slept in a ditch beside the highway?

“The sounds of trucks whizzing by still haunts me,” my daughter said over coffee and waffles. “I don’t like to eat during the day. It makes me tired afterwards. I guess that’s why I eat at night. I can just go to sleep.”

Eat, sleep and shit: the necessities of life.

Time to write letters obviously is not one of the necessities, but at least she called every now and then, and I tried to get her a new birth certificate after her passport was stolen in Mexico and she went to Guatemala without one.

How will she ever get back what with their civil war and all going on?

My mother sat my daughter down once when she was passing through west Texas.

“We sat her down’” my mother said, “told her about the things we know from TV shows.” My mother was probably relieved I didn’t call back and give her gory details about how the white truckers talked about blacks and how bad they were.

“Of course we didn’t disagree,” my daughter said, “we just wanted a ride, sat still, and listened, my backpack between my knees. When the black truck driver picked us up, all he talked about was sex with white women and showed us pictures of him and them doing it. We just sat and listened to him, too. Just waiting for our chance to get out. We didn’t think he’d try anything, but he sure would have said yes if we offered.”

It’s nice to have her home and see her friendly smile, and glad to see it’s not gone, that the rude awakening hasn’t set in and wiped her smile off forever, the way rude awakenings do when they come too early and you haven’t learned to make your own glue. The dangling beads from her neck and around her waist and ankles told me more than I wanted to know.

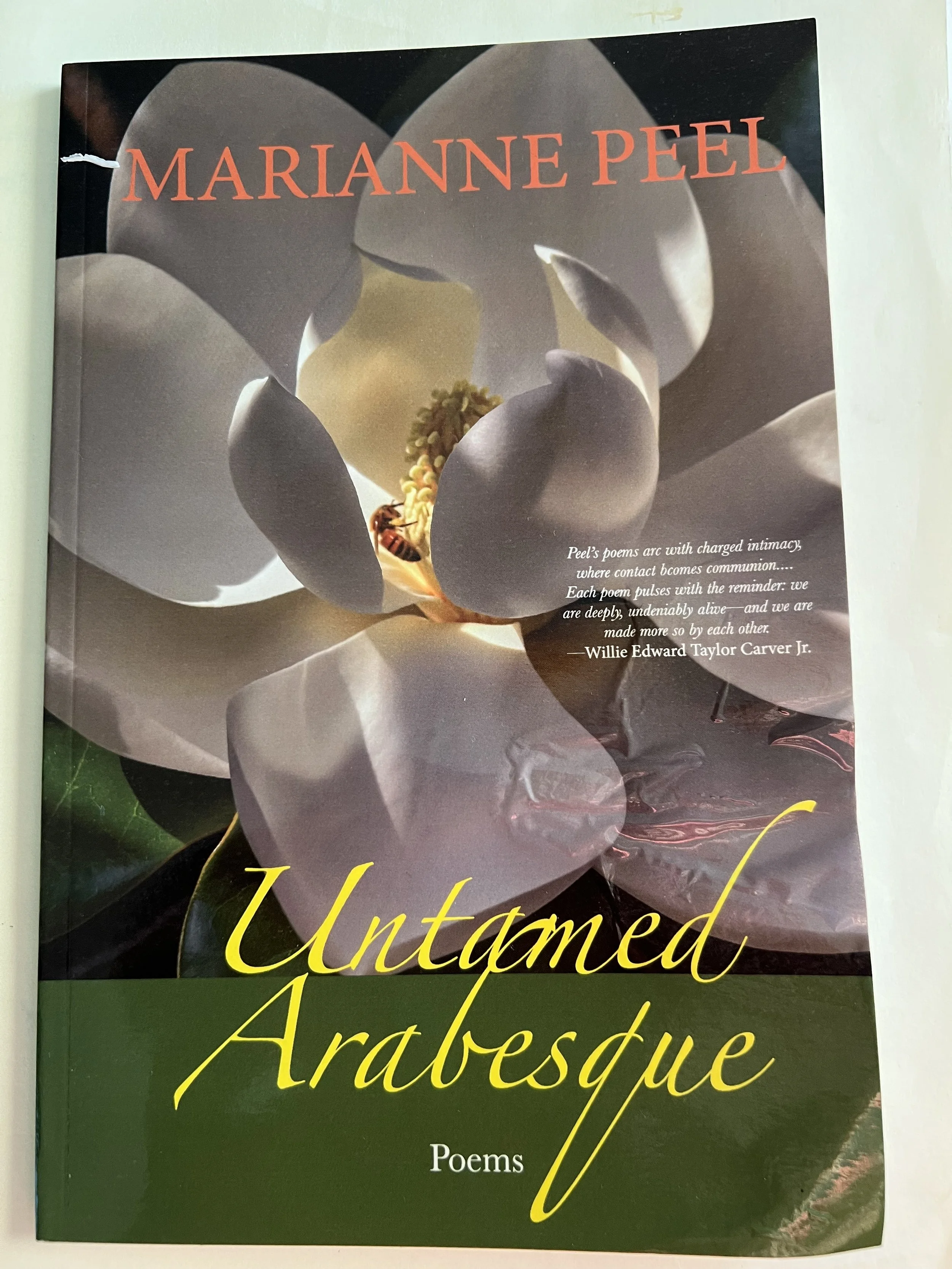

My mother was thrilled when I called and told her about my poems as long as they didn’t have fuck or weren’t about her or Daddy. So I don’t share much of my writing with her.

I’m thrilled my daughter still smiles and talks to me even though I disagree with much of what she tells me. “If I get tired during the day,” she said, “I take a toke. That gets me through.”

Loving Stoned is what I always said I’d name my book if I ever wrote about her stepfather and me and the plans and goals and dreams and decisions we made stoned during long drives to the Red River Gorge, Cincinnati or Chicago. The vision was so clear and dreams were in perfect order.

“Of course you can fuck two women and me,” I told him, stoned. I could handle anything.

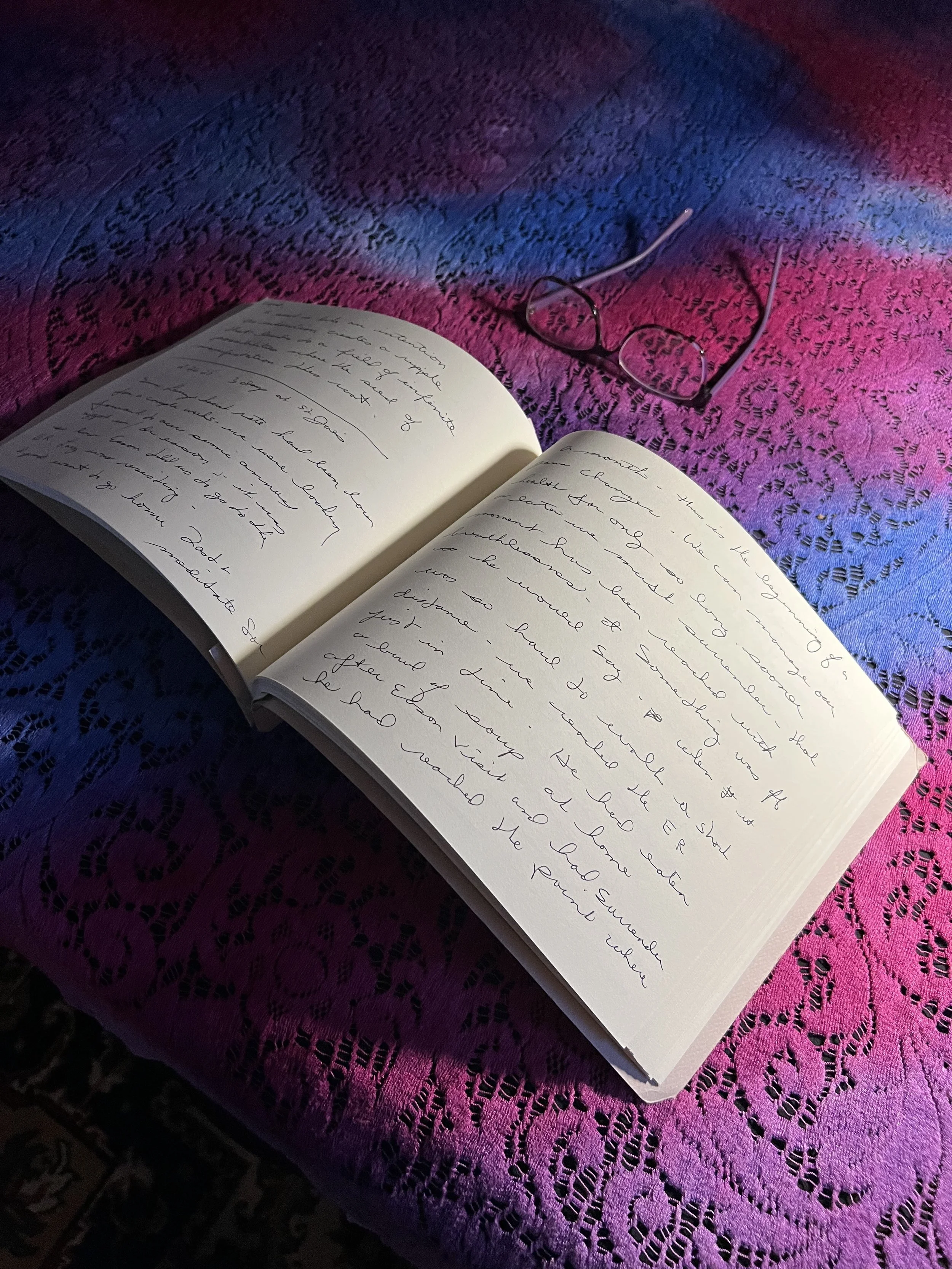

But it wasn’t all bad, don’t get me wrong. It was a really great time in my life. The waves were more intense than we realized, answers got written in journals and I never told my mother and I eventually rolled my last one when children and work and life were on the edge. That stoned clarity was more likely to push me over than put one foot in front of the other.

Of course that was then, and my mother didn’t understand, and I am the mother now and my daughter combs purple scarves in her blonde hair and if you ever tell a soul what I’ve told you, I’ll never whisper in your ear again.

“Well, you see, Mom, it's not your story anyway. It’s my story. You don’t have anything to do with it. I made it up, you see. All you did was press me through, wrap me, and look into my eyes, sing, lullabies, and tell me it’s OK to cry. So if you were thinking that it’s you, you’re wrong. It’s me and what I saw and what I don’t remember because no one remembers but what they want and they make up all the rest. Remember the time I called you and told you I had had a miscarriage? It made you sad, but I cried. I cried because I knew it wasn’t true so I called you back and told you I lied. I told you I had had an abortion. Years later, you told me you cried for months after that and that made me mad and years after that, you told me you cried for months after that, not for what I had done, but for what I must of gone through to make that decision and now I understand.”

I understand her helplessness as a mother, as I stand in the midst of my rude awakening that I really have nothing to say or control over what my children do and that the meaning of life is to sit back and watch them suffer and try to comfort myself so in the morning when the alarm goes off, I can get up and keep on going.

Mom probably won’t call me first. She wants to give me space, doesn’t want to be too intrusive and tell me what to do.

“When my kids were growing up,” my mother told me, “I wanted them to think for themselves because I never could.”

Her mother, (my grandmother) was so outspoken she told my mother everything she should do. She was a cantankerous, bitchy grandmother. I never did like her much, especially the summer as teen I’d come to visit and she berated me for running with Mexican riff raff. So I married one 20 years later. Ran off with a long-haired Mexican hippie.

“How come you never bring your husband here to visit?” My grandmother asked. I didn’t answer. That west Texas heat was hot and steamy, and I had more to do than tell my grandmother the meaning of life. Besides, she had had no intention of having a granddaughter, who grew up to think for herself.

******