About Laverne Zabielski

Living a Layered Life

back in the day, I used an iron and ironing board. Today, I use a press for that fine finished feel.

My deepest desire when designing my art to wear is to capture an essence of intrigue and statement making that exudes confidence.

I do this by living a layered life. By layering everything, as it occurs I let the thread reveal itself. And it always will if I stay true to myself, my ideas. I embrace the mantra "go with the flow." As ideas arise, I layer them onto my many canvases; my work, my art, my writing. I allow them to be part of each composition. I trust the process. Amy Krause Rosenthal says, "Pay attention to what you pay attention to." (1) I listen to my body and pay attention.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes this flow in an interview with Wired magazine as, ". . . being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you're using your skills to the utmost."

I made the decision to flow when I first discovered the art world. I didn't come from an artsy family. My father was a sergeant in the Air Force, drove a cab at night. My mother was a stay-at-home mom raising seven children.

Looking back, I see that my parents did have an eye for harmony and balance. A sense of personal style. I can see it in the the way my mother, Grace Laverne Tilson, set the table for Sunday dinner.

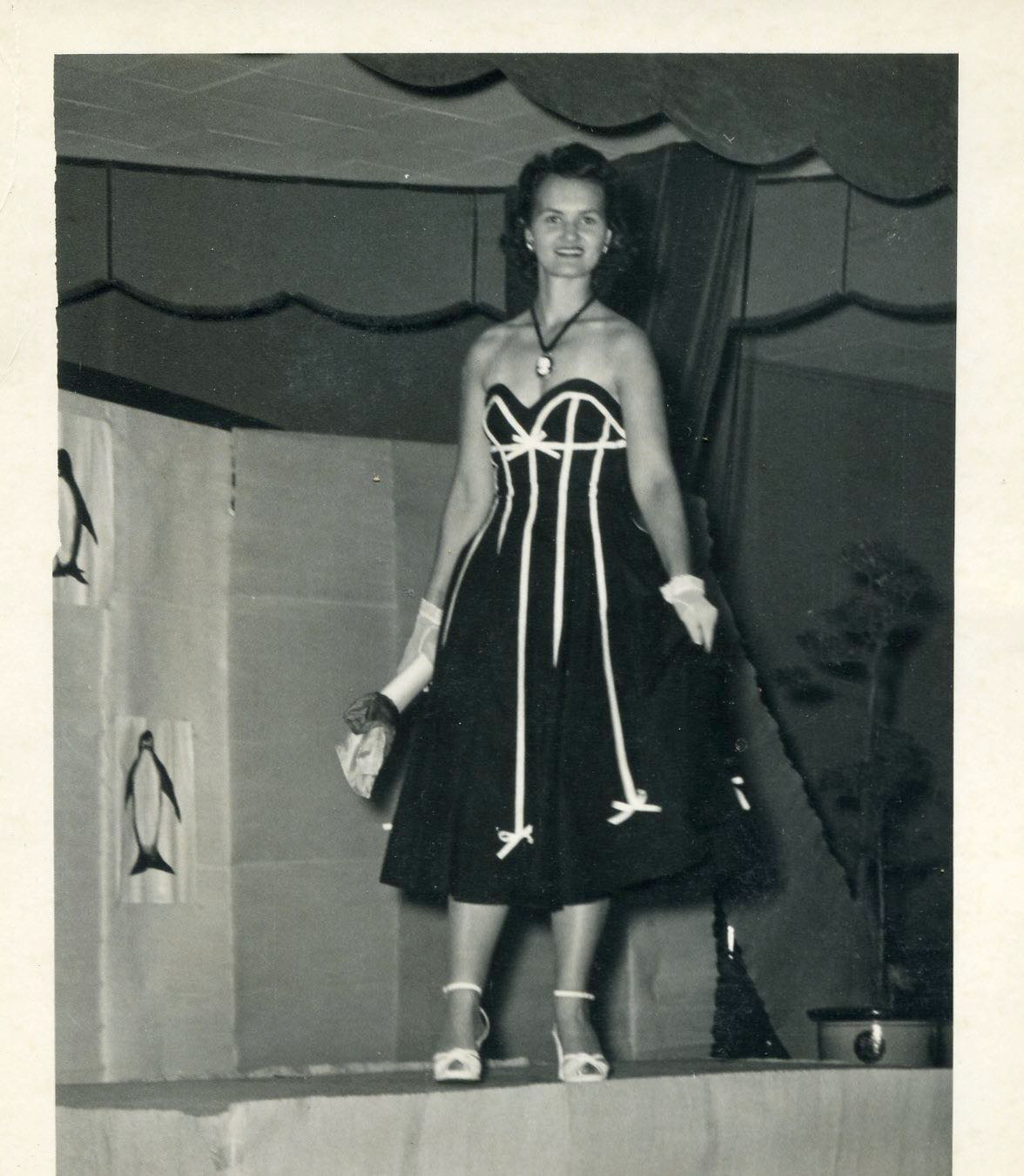

Or in the dresses she sewed. Looking at her smile I can see that she was proud.

The photographs my father, Ray Zabielski, captured revealed his aesthetic intentions and his values; Japanese children posed in front of their home in an abandoned bomb shelter, Tachikawa Air Force Base housing in the background, Dad's shadow in the field.

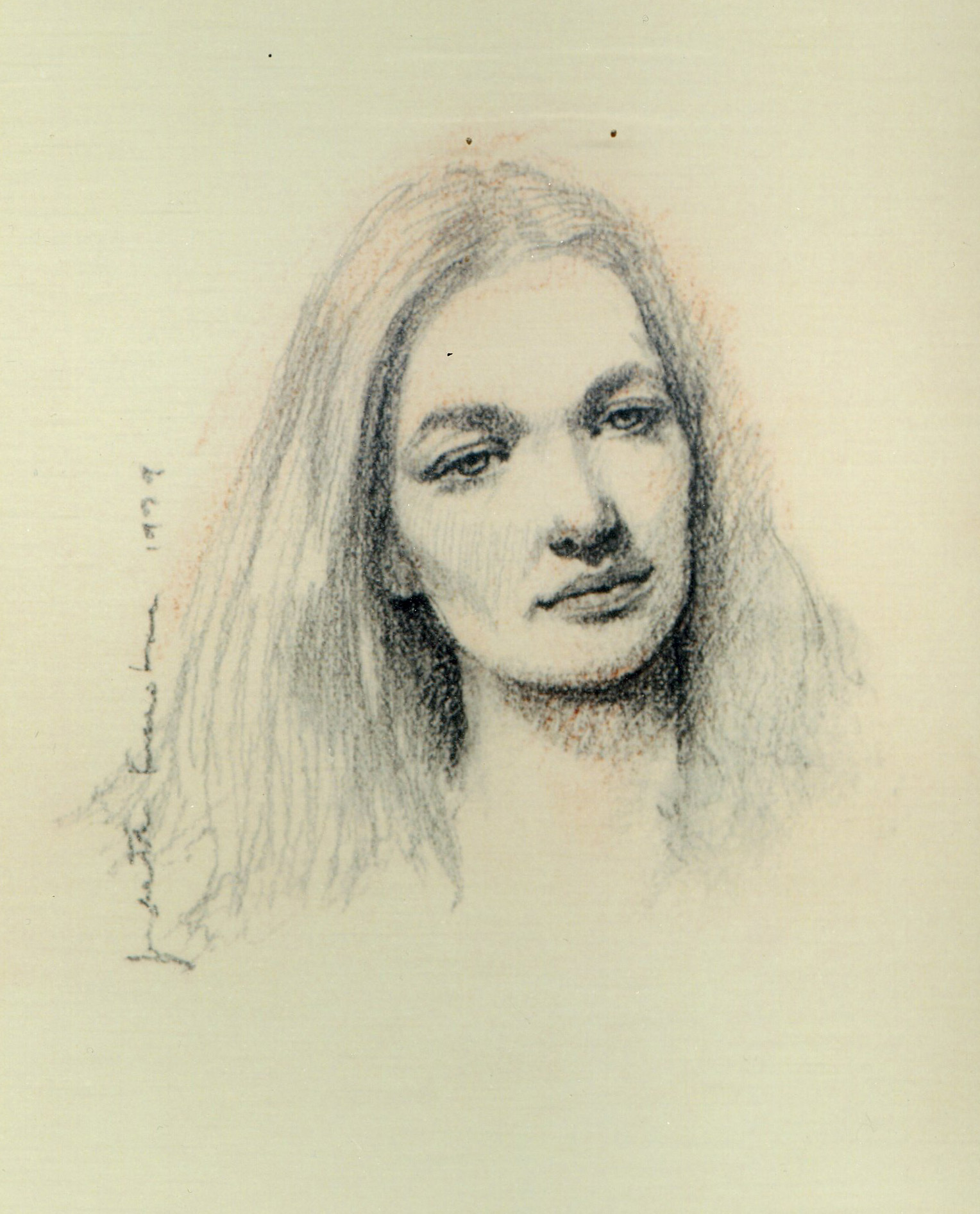

My first exposure to visual art occurred right after I started writing poetry. I met a woman who was a painter. Recently divorced, she lived on a limited budget. She had a bohemian style, wearing flowing woolen skirts and long sweaters she had knit. In her old two story house she kept the thermostat set at 65 degrees. It was chilly as I sat for the portrait she drew. It was different than a photograph. It captured a softness, a tenderness I had never seen in a photograph. It wasn't the reflection I would see in the mirror. I liked it. Her passion and expertise inspired me.

"It takes time," she said, "a lot of time to be an artist."

PORTRAIT BY JUDITH KOEHNE

I became discouraged. Time, I did not have, not with kids and a hair design business. Yet, I also had a"don’t tell me what to do" M.O. I would find a way. Writing was my art form. No matter what, I would write. Even if it meant I could only write short poems in ten minute spurts, waiting for water to boil. I had stories to tell. I was on a mission having read "Of Woman Born" by Adrianne Rich. Her edict was for women to write the truth about their experiences, no matter how painful. Through our words people will know the truth about women. Margaret Atwood call this "the literature of witness."

Flow was clear when I opened Om Hair Designs in an old English Tudor building near downtown. Every view was a work of art. The leaded windows. Archways leading from room to room. We chose a color palette for the decor and for the designers. They made intentional, artistic statements in what they wore. Black, white, burgundy and silver. Our hair design team was cohesive. We studied hair cutting and styling techniques that produced effortless designs. Our clients left confident, our way of saying sexy, sensuous, unapologetically feminine. A look women want but won't admit.

My work was my life, my art. I dressed for the day. I was, as Viola Davis said at this years Oscars, "Take me as I am." I wore the same ensemble to work, to dinner, to meetings, to a party. There was no time for “freshening up.” Take me as I am was my M.O. I wore lots of black and layered it with a palette of colors that worked for me. They enhanced my stance. A stance made manifest in the way you walk, the way you set your eyes on the road ahead, your gaze, accompanied by a smile. A confident smile that says, "Hi." A tender smile that says, "Underneath, I know we're the same. Our hearts beat. Our heart peeks out." It was the same tenderness I saw in my mother's face after she put lipstick on right before my dad came home from work.

Even shoes became part of my art form. It didn't take long for comfort to drive every decision. Standing up all day was painful.

First came wedged heels followed by color coordinated tennis shoes. Next came custom cowboy boots, handmade in Matador, a small west Texas town. They were black and matched all my outfits. "Anything goes" became my fashion statement M.O. When I dressed for the day, I chose what to wear from the shoes up. Since I had already defined my color palette, it didn't take long for "anything goes" to always work.

Black polyester jump suit with a rhinestone zipper tucked into cowboy boots worked.

Burgundy red mini skirt, white peasant blouse, and straw hat with cowboy boots worked.

Tight jeans, black chiffon tunic and silver choker with cowboy boots worked.

When asked why he like New York City, German illustrator, Christoph Neimann said, ". . . there is only one city in your life you go to by yourself and you own that place. There was no uncle, no parents that paved the way. It was like my place." (4)

That was my secret ingredient for creating the world that I owned. I had moved to a city where nobody knew my name. I could be anyone. I never had to explain myself to someone from my past. That little voice from my childhood that asked, "Who do you think you are?" Was replaced with, "I know who I am. I am Laverne Zabielski, poet, writer, hair designer."

I embraced the concept: I own this place. Not as in I own the whole city. I owned my identity that inhabited this place. Take me as I dress. In winter I rode my bike with a baby seat on the back to work. I wore a down coat that covered my artsy haircutting fashion. During the summer I rode my bike to the farmer's market wearing a flowing white, gauze skirt. I dressed for the day.

Form followed function.

Once, I went to a Halloween party after work. Someone said, "You're supposed to come in costume."

I said, "I am in costume."

Take me as I dress.

Take me as I am.

Why do I want you to experience the pleasure of statement making? For the energy and it’s uniqueness to match the uniqueness of your personality. Your uniqueness, gleaned from your full life, is your most desirable asset. Your power tool.

To many it seems, since we are naturally beautiful, which we are, it is not necessary to pay attention to our dress.

That's like moving into a house without doing any decorating.

Dressing to be seen is not a luxury.

At this stage in life, we are in our most powerful place. We know we have something to say. We are strong in our convictions and we express them through our work which we perform with integrity.

Maybe in the past we were not at ease with our body, the way we carried ourselves or the way we talked about beliefs, opinions or values. Now we are beyond all that.

Let's work together and acknowledge that it’s time for adventure and serenity, calm and intrigue. It's time for statement making.

As we age the sensuality we manifest and express is not meant to seduce another, it seduces our wise woman within. And she shines forth to others, brightening their day when they gaze upon her. Unfortunately, by equating sensuality with sex, our culture denies our embracing all our senses. Our curvilinear lines, our soft skin, our fragrance, our sweet voice. Confidence is made manifest when we no longer resist, defend or justify our sensuality. It simply is.

We know life is complicated. Like ourselves. We know life needs to be experienced. Like ourselves

I will be your “go girl.” I will whisper your beauty. It is time now to let go and unleash. Express yourself fully, boldly. After all, you are in control. You have hutzpah and it’s hungry. Let me help you feed it.

The woman desiring to feed her hungry hutzpah knows.

She knows who she is

and

where she is going.

You are the kind of woman who is full of wisdom. You are presenting yourself to life, vibrant and bold. All the color, all the flavors of emotions, creativity, of a life lived are coming out. Your friends gather around. You have wisdom to share. Your elixir is desired.

Everything you’ve gone through in your life, your joy and sorrow has made you rich with life’s color. You have become the full open flower, the orchid, the rose.

I give you another tool to express yourself, to bring out your fullness, to unleash what you really want to give to the world.

What I have for you is not a piece of clothing. It is art. It makes you feel lovely, elegant, playful, sensual, beautiful, and colorful. It fills you with energy. It presents the unique you. Your most valuable asset. Your power tool.

Your uniqueness is why people listen to you, want to know more about you.

What I have for you

Is a designer statement piece.

How I came to be who I am and do what I do

IMPRESSION

It was the lipstick floating on toilet paper that gave my mother away. When she put that red across her lips, it not only changed her face, it changed her stance when she stood at the stove and stirred.

grace laverne tilson zabielski 1946

FOCUS

In 1998 a friend suggested I learn to dye fabric, then I could cover my books in silk. I enrolled at

the University of Kentucky. Six weeks after starting classes my 26 year old son had a

paralyzing accident.

When I first received the call from the emergency room nurse on September 11, 1998, I assumed she was telling me the worst so I wouldn’t be getting my hopes up. I listened as she stated Donnie's condition: collapsed lung, paralyzed, no brain damage. I knew he would pull through. And I knew I was strong and in control.

I marched through those steel gray emergency room doors as if to say: Come on Donnie we can handle this, let’s go on home. Of course we couldn’t—not with all those tubes and that paralysis. The first thing he said to me, the very first thing was, “I’m sorry.” That was before all the tubes were inserted and I’m sure neither one of us knew it would be weeks before any real conversation would take place and that I would learn to read lips and tell him things from some place inside me that could only be spoken then.

Several weeks later as he became stronger and only a few tubes remained in his arm and his throat and other hidden places under sheets that I could never see, we moved on to the mundane. Who will care for his dog while he’s in the hospital and can he live on his own, even if he is paralyzed? I didn’t even ask, can he? I simply assumed.

"Should I quit school to take care of him," I asked myself. When I realized this was forever and we both had to learn to deal with it, I decided to stay in school and learned the most important lesson of my life: focus.

The only way I could manage classes and intensive care was going to be by picking one thing. I chose the Arashi Shibori technique for dyeing fabric. Not only did I make books, I began designing collections to wear at my performances. What I discovered was that when you wear art it changes your stance. No matter how you wear it, or fold it up in your lap, it is beautiful and has energy.

MOTHERING

We got a note from Danny John’s teacher. I mean, he’s only three and a half.

“It’s the sillies,” she said. “He’s got the sillies. Won’t settle down and do his work. He’s just too silly. Doesn’t seem to know what is socially unacceptable.”

So this is how he turned out—too silly. “What is socially unacceptable, anyway?” I ask.

“Playing in his food,” she answers.

“Interesting,” I say, “considering his favorite friend is an artist and she calls food ‘art’ and Hershey’s syrup ‘food paint.’ Maybe he’s making food art?”

“And about his hair. Maybe it would be better if he didn’t get it cut so short. It disrupts the class. The children gather around him. ‘What did you do to your hair?’ They ask and they all want to touch it.”

Oh my god, they want to touch him? He’s the one who wants it cut so short. Do you think it could be he likes being touched?

So this is how he turned out—too silly, having too much fun, and he likes to be touched.

What is socially unacceptable, anyway?

WORK

Johnny does important work at eighteen months. I wash the kitchen floor. I’m with Johnny and with Johnny is where I want to be. I wash the kitchen floor and get it clean. Johnny climbs up on a chair he has pushed up to the counter. He gets a dishrag and brings it to me. He wants to help. He has important work to do. He has his rag and he wants to do his important work of washing floors. I concentrate on washing the kitchen floor as he concentrates on washing the kitchen floor.

Nothing is more important than anything else, and the floors are clean. I begin to prepare the dinner. I take out the chicken, wash and dry it and Johnny pushes the chair up to the counter to do important work. He takes the dishes out of the dish drainer and I brown the chicken. He puts the dishes in the sink, and I brown the chicken. Johnny does the important work of putting clean dishes back into the sink.

I walk out the back door to put the dirty rags in the laundry and Johnny closes the dryer door for me. The towels are dry. I take them out of the dryer and Johnny closes the dryer door for me. I open the dryer door, put the wet towels in and Johnny closes the dryer door for me. Johnny does the important work of closing the dryer door. I add spices to the chicken. Johnny sleeps as I write.

DIVORCE

July 1984

Sitting at the kitchen table, my face is on fire. Allergy? Or is it stress? I can barely write. My wrists won’t move. I just took Dana to the airport. She’s been living with her father for the past nine years. One week just wasn’t enough. I cried for being such a shitty mother, for leaving her when she was five, for her wanting me to come back and I never did, for not hearing her sing in the choir, for not seeing her lead cheers or play basketball, for not being there when she came home from school, for not listening to her tell me what’s going on in her life. Tears rolled down my face. Salt set my skin on fire. One week just wasn’t enough.

DRESS UP

1955

First, my mother made sections, laid the rag across her finger and combed smooth the silky strands, wrapped them down, under, up and around, tying a knot then sliding her finger out. The next morning she untied each one—chocolate swirls. Pulling them back, I sat, pretty,

VISION

When I feel the wind on my skin there is an ache in my chest that calls to me, tugging at my arms, pulling me into it’s sensuous embrace. I pack silk and dye in preparation for my journey to the farm. We are moving there to grow old. In small, incremental stages, we will put our life behind us, piece by piece.

Each trip down I carry one belonging with me. Today I’ll take my flower-covered Sadler teapot. I’ll leave one artifact behind; the old wooden porch swing by the back door. I’ve asked each child to pick one thing and take it now; a piece of jewelry that hangs on my walls, a painting from my art class or one of my handmade artist books.

Last week we installed the wood stove. Larry sculpted a glistening copper chimney. Later we climbed the roof, nailed metal roofing down, then gathered wood off the mountain. And stacked a woodpile.

During the evening I processed the silk I had dyed earlier. Wrapped in newsprint, heat set the dye as the silk steamed in the old canner on the wood stove. I love hanging the freshly rinsed silks in the barn, the contrast between the rawness of the wood, its roughness and the softness of the silk, sensuously moving as the wind blows through the cracks in the barn. I am in awe of the individually wrapped and twisted silks, saturated with dye that hang from nails spread across old planks— the way the dye drips on the paper beneath making another artwork all of its own from the colors that bleed and drip into curvilinear lines making soft amorphous shapes.

It doesn’t matter that the barn is dirty. It does not interfere with the process. I have deliberately chosen a process that can be flexible. These are the things that make the rhythm of my art apparent. The way I swing the big barn doors open and prop them with an iron rod. The way I move up to the long table Lester tied tobacco on when he owned the farm. The way I envision silk eventually hanging like tobacco from the ceiling, blowing in the wind making a silent sound instead of the rustle of dried tobacco leaves.

My dance saunters over to the wood stove. I stoke the fire while silk steams, setting the dye, keeping the color brilliant. The hues vary as the seasons change and I gaze through the open barn doors onto the valley and let the colors in the field, the trees, or the reflections in the pond guide me in the choices of colors for that day.

This is the gift I love most to share—my ability to arrange life so that art is always there to be woven in as time permits. And time will always permit. One must be ready.

WHY I MUST MAKE ART

I began as a writer, writing the truth about my experiences, no matter how painful. As my children became teenagers, I became a visual artist. This is when I learned having something to create in process at all times will get you through the hard times. While much thought and contemplation goes into visualizing a piece of art or project, the actual tasks for completion are somewhat routine and can be completed in the midst of chaos; wrapping, dyeing, steaming, rinsing, ironing and then finishing the edges to create truly wearable art which is vividly layered and intrinsically contains the stories of my life.

BIO

In 2004 I received my MFA in writing from Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky. I studied Shibori silk dyeing with Arturo Alonzo Sandoval at the University of Kentucky. Fiber art and artist books have been exhibited at The Friedman Chapman Gallery in Louisville, KY, MS Rezny Gallery, The Singletary Center for the Arts, University of Kentucky, Carneigie Center for Literacy and Learning and Artsplace Gallery, Lexington, KY, and Claypool-Young Art Gallery, Morehead State University, KY. Creative non-fiction essays and poetry have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including: The American Voice, High Performance, The Sun, Now and Then, and Southern Exposure. "The Garden Girls' Letters and Journal," my memoir, was published in 2006 by Wind Publications.

Read my Artist Statement.

HOME

Currently I live in a cabin in the foothills of the Appalachian mountains. My inspiration comes from hiking in the woods and trying to figure out how to capture the colors I see.